APOLOGETICS HAS ITS ORIGIN in Greek rhetorical argument where the proponent presents an ordered defense, including the reasons he or she has for belief in a particular philosophy or religion. There are several ways in which an apologetic can be fashioned. Methods specific to an apologetic for Christianity are Classical, Evidential, Cumulative, and Presuppositional. Each has its own merits and is often dictated by the circumstances faced by the apologist. I believe Cumulative apologetics is the best method for defending Christianity in a post-Christian culture.

Cumulative Case Apologetic

The Cumulative Case method takes a “best explanation” approach by presenting interconnected evidence and arguments that serve as an accumulation or preponderance of proof which (although not necessarily in succession) ultimately builds to a sound conclusion. The desired result of the Cumulative Case method is more than merely drawing a line in the sand. As with circumstantial evidence in a criminal proceeding, the Cumulative Case apologist compiles numerous types of evidence that point to the probable existence of God based on available evidence. This is known as abductive argument, a form of logical inference, that differs from standard inductive or deductive reasoning.

As a Cumulative method apologist, I strive to obtain information through unambiguous and reputable sources, such as “peer-reviewed” articles and papers. Conclusions reached by a Cumulative method apologist are based upon a preponderance of the evidence, leading to the most likely (or most probable) explanation, rather than beyond a reasonable doubt. True to the Cumulative method, Lee Strobel investigated the soundness of Christianity’s claims through extensive research. He interviewed numerous leading scholars and authorities, and applied various types of proof to the case for Christianity—eyewitness, documentation, corroboration, rebuttal, scientific. This method is well-suited for presenting the concept of one God (theism) and, specifically, the story of man’s sin and redemption that lies at the core of the Christian faith. Strobel said, “I was a narcissist, I was a hedonist, I was a heavy drinker, I was self-absorbed, self-destructive in many ways, I was an atheist. I was successful in my career; I was Legal Editor of The Chicago Tribune, which is our biggest newspaper between the two coasts” (1).

The Cumulative Case method has been used by several distinguished Christian apologists, including, G.K Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, Richard Swinburne, Paul D. Feinberg, and Lee Strobel. Feinberg believes the model for defending Christianity is not found in a formal argument of philosophy or logic; instead, it is found in law, history, and literature. Cumulative apologetics supports all methods for determining Truth, including personal (subjective) experience, the universal sense of morality, the role of the Holy Spirit in revelation, and historical or archaeological confirmation. The Cumulative approach seeks to show that the story of Christianity makes better sense of the evidence than any other worldview.

I use the Cumulative Case method because it provides the best opportunity for a proper conversation about the existence of God (establishing theism), then building toward a case for the story of Christianity. Attempts to establish the truth of God’s existence by saying “God is necessary, therefore He must exist” typically fails because it is supported by an argument the atheist will not accept as true. However, through a relaxed standard, it is possible to have a conversation regarding alternative explanations for God, origin of life, and related topics. I am particularly appreciative of the approach of C.S. Lewis.

C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was an author and Christian apologist who is best known for his Chronicles of Naria series and his seminal book Mere Christianity. Through a combined study of philosophy, literature, and theology, he came to believe in the God of Christianity. He uses the term “mere” in the context taken from Old English meaning “pure” or “unmixed”—indicating an understanding of core Christian doctrine unencumbered by secondary denominational teaching (2).

“Christianity is like a hall out of which doors open into several rooms. If I can bring anyone into that hall I shall have done what I attempted to do. But it is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals. The hall is a place to wait in, a place from which to try the various doors, not a place to live in” C.S. Lewis (3).

The story of Christianity is fundamentally about salvation, redemption, and restoration. Clearly, part of this restoration involves a change in one’s way of thinking. The apostle Paul said believers must be “transformed by the renewing of your minds” (see Rom. 12:2). Lewis believed this transformation is possible because of man’s universal desire for divinity—a hunger for something beyond this world, which he called “transcendent desire” (4). He expressed this desire quite nicely in Till We Have Faces when the character Psyche tells Orual, “The sweetest thing in all my life has been the longing—to reach the Mountain, to find the place where all the beauty came from…my country, the place where I ought to have been born. Do you think it all meant nothing, all the longing? The longing for home? For indeed it now feels not like going, but like going back. All my life the god of the Mountain has been wooing me” (5).

Paul D. Feinberg

Paul D. Feinberg agrees with Lewis that morality (or the moral law) is a means for showing something universal beyond sense experience. The moral law “…is a real thing that is independent of us, not something made up by us” (6). It is after coming to believe in a moral law (and a lawgiver), the Fall of mankind in the Garden, and the universal depravity of man, that we are ready for the Christian worldview. We can then develop the capacity to see Scripture as revelation. Through Scripture, one comes face to face with Jesus Christ. Feinberg is bold in his assertion that “…within the Christian revelation there are claims of an empirical sort that can be tested” (7).

The resurrection of Christ from the dead was verifiable through the empty tomb (see John 20:1-10). Further, there were numerous sightings of the risen Christ after His resurrection (see Luke 24:13-32; John 20:19-20; John 20:26-29; 1 Cor. 15:6). Virtually every element of the crucifixion is described in detail by Isaiah in the passage often referred to as the “gospel according to God” (see Isa. 52:13-53:10). By choosing an informal argument for the existence of God, using varying elements as evidence, the emphasis moves off one’s individual (subjective) convictions and focuses instead on explanation that is beyond the apologist. Feinberg says this allows the apologist to start with any element of the case, and depending on the response, appeal may be made to some other element to support or reinforce the claim that Christianity is true (8).

Certain universal tests for truth can be applied to an argument. Ravi Zacharias said philosophy and religion use identical standards regarding the value of a worldview: (i) is it logically consistent; (ii) is it empirically verifiable; and (iii) is it experientially relevant? Feinberg uses consistency, empirical fit, comprehensiveness, simplicity, livability, fruitfulness, and conservation as his litmus test. Groothuis adds, “The logic of truth begins with the logic of the law (or principle) of non-contradiction (9). As Aristotle noted, nothing can both be and not be at the same time in the same respect. Groothuis concedes that a sentence cannot be either true or false if it has many meanings, each of which has its own truth value. But, as he notes, this objection misses an important point because the law does not address questions of interpretation. Instead, it addresses the truth value of a statement once its meaning has been determined. At that point, the statement can only be true or false (10).

Christians have the internal or subjective witness of the Holy Spirit regarding God’s truth. Jesus said of the Holy Spirit, “But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you” (John 14:26). The Holy Spirit bears witness with a man’s spirit that he is a child of God (see Rom. 8:16). God’s Spirit convicts or convinces unbelievers of sin, righteousness, and judgment (see John 16:8-11). He also appeals to conscience (see Rom. 2:14-16) and creates in every man a sense that there is a God (see Rom. 1:19). Feinberg writes, “The fact that the Spirit witnesses to our spirit that we have believed the truth explains the tenacity and stubbornness of the believer’s faith in God” (11).

Some apologists see the Cumulative case method as an amalgam of Classical, Evidential, and Presuppositional methodologies. I don’t believe this to be so. Rather, I think Cumulative apologetics is best noted for how it allows for the careful weighing of all available data in support of the biblical story of God, Creation, and man’s place in it. Steven Cowan raises an excellent point: “…the nature of the case for Christianity is not in any strict sense a formal argument like a proof or an argument from probability” (12).

Storytelling as an Apologetic

Lewis realized that the two hemispheres of his life—imagination and reason—could be united in the story of Christianity. Indeed, his transformation from theist to Christian occurred when he saw Christ’s sacrifice as a story that actually happened. Stories matter. Part reason and part imagination, they allow for a fuller response to the subject matter. Kevin Vanhoozer said, “At the heart of Christianity lies a series of vividly striking events that together make up the gospel of Jesus Christ” (13). In fact, the drama of Christian doctrine begins with creation, and continues through God’s election, the climactic act of the incarnation of Jesus Christ, the sending forth of the Holy Spirit into the body of believers, and the final consummation of all things. Sean McDowell smartly remarks that the Christian calendar enables the church each year to relive this drama, and in a sense to reenact it, in sequential order. He says, “The power of story allows the apologist to transform abstract truth into something that the reader or listener can engage with” (14).

J.R.R. Tolkien aided Lewis in understanding myth as a symbolic story used to express higher truths that cannot be captured in literal language (15). Once Lewis saw Jesus Christ as the transcendent coming into the world of facts, he was able to focus on the Incarnation. He responded to his own personal calling by using his unique God-given talents to tell the story of Christianity as only he could tell it. The key here is direct dialog. Groothuis reminds us that the spirit of persuasive dialog was alive in the teaching and preaching of Paul throughout the book of Acts (16). All the messages recorded in Acts had a strong apologetic content (17). Lewis’ stories, especially the Chronicles of Narnia series, are also alive with meaning.

Moral and Epistemological Relativism

Western culture faces yet another existential crisis in the twenty-first century amid a Zeitgeist of religious pluralism. The attitude toward organized religion changed drastically following the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Religious fundamentalism was suddenly seen as a threat. Any successful conversation today about theism and Christianity must respect these individual concerns while also presenting an accumulation of arguments and supporting evidence that suggests the probability that the story of Christianity is true. Richard Dawkins, a prolific atheist who has set his sights particularly on Christianity, said after 9/11, “Science flies you to the moon, religion flies you into buildings.”

Moral relativists claim that morality is determined through cultural and individual interpretation of what is appropriate behavior. Francis J. Beckwith and Gregory Koukl believe subjective moral truths “…are preferences much like our taste in ice cream. The validity of these truths depends entirely on the one who says, ‘It’s true for me if I believe it'” (18). Relativism is revisionist because it seeks to redefine what it means to be moral. It rejects the notion that morality is a supremely authoritative guide, containing a code of conduct that directs how things should be, and that it is universal in scope. Groothuis believes the dependency thesis—that morality is dependent on culture—takes a half-truth and inflates it into a whole lie. The postmodern mind believes that morality is contingent and revisable, based solely on cultural factors (19).

With today’s religious pluralism, it has become unacceptable to claim that God has revealed Himself decisively in Jesus, or that Christ is the only way to heaven. Post-Christian culture has its roots in Christian ideals (its “distant past”) and perhaps still follows basic Christian values, but rejects the authority of Christianity and its influence over morality or culture. Feinberg says postmodernism boasts of the death of God while trying to retain some general idea of meaning and value. But Feinberg adds, “When God dies, absolute relativism follows” (20) How, then, can there be any distinction between good and evil? He said in the end, this way of thinking results in nihilism. It involves the subversion of everything that was once thought to be holy. It denies all meaning, all purpose, all ethical and aesthetic norms. Paul M. Gould said in an article for Christianity Today, “Effective apologetics today requires a genuine missionary encounter” (21). How to have that genuine encounter is what drives the work of cultural apologetics.

Cultural Engagement

As an apologist, if I fail to understand those I seek to reach with the gospel, it will not be possible to engage in profitable dialog with that person. Further, if I rely too heavily on typical theological arguments and archaic terms, the message will be misunderstood. In a post-Christian society, talk about Jesus is no different from talk about Muhammad or Yahweh. Admittedly, these types of conversations are difficult in a culture that denies moral absolutes or a supreme being. I agree with Gould that cultural apologetics is “….the work of establishing the Christian voice, conscience, and imagination within a culture so that Christianity is seen as true and satisfying” (22).

J. Warner Wallace, a homicide detective who teaches the method of applying criminal investigation to the case for Christ, suggests a methodology known as abductive reasoning to determine the caliber of evidence available in a particular argument. He says, “While it is interesting to imagine the possibilities, it’s important to return eventually to what’s reasonable, especially when the truth is at stake” (23). When presented with two competing explanations that seem similarly reasonable, Wallace suggests applying the truth tests of viability, simplicity, depth, consistency, and superiority. As Koukl notes, apologists defend the faith, defeat false ideas, and destroy speculations. Sadly, however, postmodernists often ignore facts, engage in logical fallacy, become belligerent, or simply give up and walk away. For Koukl, “tactics” amounts to a hands-on choreography of the particulars.

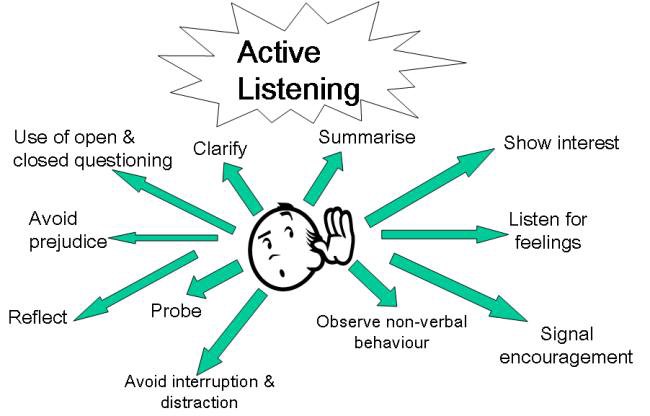

Today’s “argument culture” has become prolific across all media. The apologist must engage in conversation with those who often take a rather strong opposition to Christianity. McDowell said he has “…watched our culture simultaneously lose the ability to have respectful conversations and become more hostile to Christian beliefs” (24). The first step is to listen before giving an answer. Proverbs 18:13 says, “If one gives an answer before he hears, it is his folly and shame.” Asking questions of one’s opponents establishes an atmosphere of respect and civility. It allows for a constructive conversation.

Concluding Remarks

Apologetics necessarily involves cultural engagement, and the apologist must take his or her culture “as it comes.” A fine place to start would be to ask, “What do you make of this man called Jesus?” C.S. Lewis spoke highly of intuition as the way to start knowing. He said, “If nothing is self-evident, nothing can be proved” (25). If everything is determined to be true, then nothing would be true. As with any important topic, conversations about religion and truth require diplomacy, respect, humility, and a sense of fair play. Lewis said, “The man who agrees with us that some question, little regarded by others, is of great importance can be our friend. He need not agree with us about some answer” (26). This shows a willingness to be diplomatic when discussing topics as sensitive as religion or the meaning of life.

The Cumulative Case method takes a “best explanation” approach by presenting interconnected evidence and arguments that serve as an accumulation or preponderance of evidence which, although not necessarily successive, ultimately builds to a sound conclusion. It is important for the apologist to maintain ground when defending the story of Christianity without causing the skeptic or nonbeliever to shut down. Christianity can be defended through extensive research, interviewing leading scholars and authorities, and applying various “types” of proof—eyewitness, documentation, corroboration, rebuttal, scientific. As believers, Christians are to be well-prepared for giving a defense (apologia) for their faith in the story of Christianity. The approach must always be one of gentleness and mutual respect, but as Christians we must be willing to have the conversation (see 1 Pet. 3:15).

Steven Barto, B.S. Psy., M.A. Theology

Footnotes

(1) The Case for Christ: Journalist Lee Strobel’s Personal Journey.

(2) Michael L. Peterson, C.S. Lewis and the Christian Worldview (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 8.

(3) C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: HarperOne, 1980), xv.

(4) Peterson, Ibid., 32.

(5) C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces (New York: HarperCollins, 1984), 75-6.

(6) Paul D. Feinberg, “Cumulative Case Apologetics,” Five Apologetic Views (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000), 164.

(7) Ibid., 165.

(8) Ibid., 152.

(9) Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2011), 46.

(10) Groothuis, Ibid., 48.

(11) Feinberg, Ibid., 159.

(12) Steven B. Cowan, Five Views on Apologetics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000), 14.

(13) Kevin J. Vanhoozer, The Drama of Doctrine: A Canonical Linguistic Approach to Christian Theology (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005), xi.

(14) Sean McDowell, A New Kind of Apologist: Adopting Fresh Strategies, Addressing the Latest Issues, Engaging the Culture (Eugene: Harvest House Publishers, 2016), 115.

(15) Peterson, Ibid., 7.

(16) Groothuis, Ibid., 42.

(17) Ajith Fernando, Acts: NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998), 30.

(18) Francis J. Beckwith and Gregory Koukl, Relativism: Feet Firmly Planted in Mid-Air (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998), 28.

(19) Groothuis, Ibid., 333.

(20) Feinberg, Ibid., 169.

(21) Paul M. Gould, “What is Cultural Apologetics?” Christianity Today (Apr. 15, 2019). URL: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2019/april-web-only/what-is-cultural-apologetics-paul-gould-excerpt.html

(22) Gould, Ibid.

(23) J. Warner Wallace, Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels (Colorado Springs: David C. Cook, 2013), 36.

(24) McDowell, Ibid., 22.

(25) C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: Macmillan, 1955), 53.

(26) C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1960), 96.