When Jerry Falwell died on May 15, 2007, CNN anchor Anderson Cooper asked the caustic atheist Christopher Hitchens (1949-2011) for his reaction. Cooper said, “I’m not sure if you believe in heaven, but, if you do, do you think Jerry Falwell is in it?” Hitchens held nothing back. He took a deep breath, smirked, and said, “No. And I think it’s a pity there isn’t a hell for him to go to.” Cooper was taken aback. “What is it about him that brings up such vitriol?” Hitchens said, “The empty life of this ugly little charlatan proves only one thing, that you can get away with the most extraordinary offenses to morality and to truth in this country if you will just get yourself called reverend.” Hitchens told Cooper he thought Falwell was “…a bully and a fraud” who was essentially a Bible-thumping huckster.

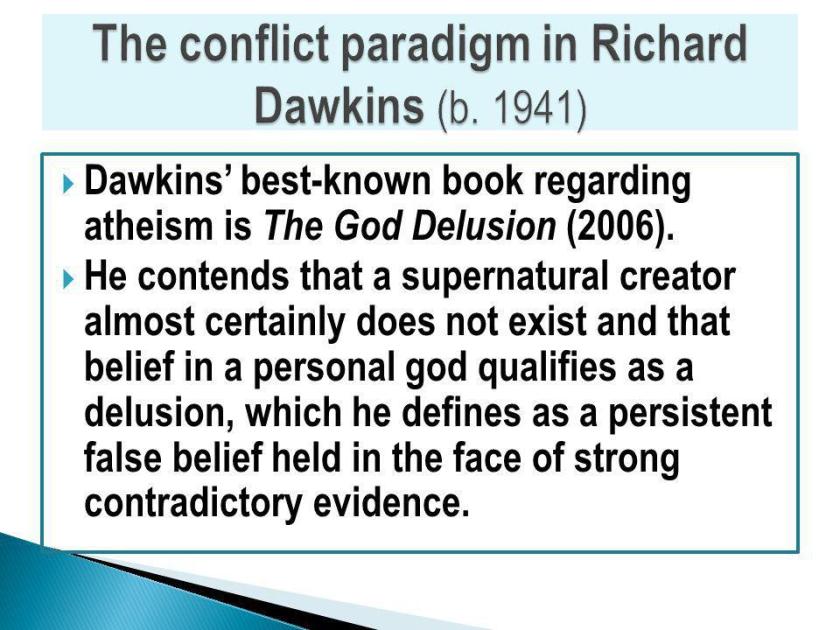

I was introduced to Christian apologist Dinesh D’Souza in my World Views class at Colorado Christian University. One of the weekly assignments included watching a debate between D’Souza and Christopher Hitchens. I was shocked at the amount of venomous, loaded, sarcastic language Hitchens kept throwing his opponent. Hitchens always came across as a bombastic bully better at delivering witty zingers than compelling arguments. D’Souza writes, “A group of prominent atheists—many of them evolutionary biologists—has launched a public attack on religion in general and Christianity in particular; they have no interest in being nice.” He notes a comment made by Richard Dawkins in his book The God Delusion, displaying Dawkins’ anger at God:

The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infaticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.

In a Christianity Today article dated March 13, 2008, Tony Snow writes, “There are two types of Christian apologetics. One makes the positive case for faith; the other responds to critics. Dinesh D’Souza’s delightful book, What’s So Great About Christianity, falls into the second category. It sets out to rebut recent exuberant atheist tracts, such as Christopher Hitchens’s God Is Not Great and Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion.” Snow notes that these so-called militant atheists tend to combine argument with large doses of bitter biography. Hitchens has gone so far as to state, “…religion poisons everything.”

Dr. David Jeremiah, in his book I Never Thought I’d See the Day!, said, “When I write of the anger of the atheists, I am not primarily referring to the classic atheists such as Bertrand Russel, Jean-Paul Sartre, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud. The atheists I am writing about are the ‘New Atheists.’ The term ‘new atheism’ was first used by Wired magazine in November 2006 to describe the atheism espoused in books like Daniel Dennett’s Breaking the Spell, Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion, Lewis Wolpert’s Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast, Victor Stenger’s The Comprehensible Cosmos, Sam Harris’s The End of Faith, and Christopher Hitchens’s God is Not Great.“

WHY ALL THIS ANGER?

How can people be so angry with God if they do not even believe He exists? Moreover, why would those most indignant about God feel such compulsion to literally preach their anti-God religion with the type of zeal we typically see from evangelists? Do they consider atheism to be their religion? Today’s front line atheists have truly ramped up the volume of their objections. They once held private their personal opinion that God does not exist. Today, they find it necessary to go on talk shows and lecture circuits announcing their belief in loud, shrill, militant voices.

The Pew Research Center (2019) published an article indicating that in the United States the ages 14–17 are very influential in terms of an individual adopting atheism. Of those who do embrace unbelief in the United States, many do so in their high school years. The average age group when most people decide they do not believe in God is 18-29 (40%). Theodore Beale declared, “”…the age at which most people become atheists indicates that it is almost never an intellectual decision, but and emotional one.” The Christian apologist Ken Ammi concurs in his essay The Argument for Atheism from Immaturity and writes, “It is widely known that some atheists rejected God in their childhood, based on child-like reasons, have not matured beyond these childish notions and thus, maintain childish emotional reactions toward the idea of God.” It is likely some great trauma or loss has caused the young atheist to not only reject God but to be filled with anger and resentment.

Men such as Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and Sam Harris are known for taking a look-back-in-anger, take-no-prisoners type of atheism. They, and most other active but not-so-famous atheists, reject the term “militant,” and refuse to explain their anger. Antony Flew, atheist-turned-believer and apologist, said, “What was significant about these [men’s] books was not their level of argument—which was modest, to put it mildly—but the level of visibility they received both as best sellers and as a ‘new’ story discovered by the media. The ‘story’ was helped even further by the fact that the authors were as voluble and colorful as their books were fiery.” Their delivery sounds a lot like hellfire-and-brimstone preachers warning us of dire retribution, even of apocalypse.

It’s obvious that atheists in the West today have become more outspoken and militant. The “average” atheist balks at the term militant, claiming it has no place in non-belief; only in radical, violent extremists like the Christians of the Crusades and Islamic terrorists. Fine. Let’s take a look at the meaning of militant: “combative and aggressive in support of a political or social cause, and typically favoring extreme, violent, or confrontational methods.” No, these new atheists do not seem to be violent, but you don’t have to be violent to be militant. They are surely combative and aggressive, often using rude, brutish, insulting confrontation in lieu of substantive comebacks. Dinesh D’Souza says what we are witnessing in America is atheist backlash. The atheists thought they were winning—after all, Western civilization has adopted pluralism and moral relativism—but now they realize that, far from dying quietly, Christianity is on the upswing. This is precisely why the new atheists are striking back, using all the vitriol they can command.

For example, consider the title of some of the books the new atheists have written:

- The God Delusion—Richard Dawkins

- The End of Faith—Sam Harris

- God: The Failed Hypothesis—Victor Stenger

- God is Not Great—Christopher Hitchens

SOMETHING IS LACKING IN THIS NEW ATHEISM

Dawkins, Hitchens, Harris, and others refuse to engage the real issues involved in the question of whether God exists. None of them even address the central grounds for positing the reality of God. Flew notes Sam Harris makes absolutely no mention of whether it’s possible that God does exist. Moreover, these new atheists fail to address the pesky question Where did the matter come from that forms our universe? They don’t discuss rationality, consciousness, or conceptual thought. I’d love to know where they believe our intellectual capacity, as well as metacognition—thinking about thinking—and who we are and what life really means came from. Neither do they present a plausible worldview that explains the existence of law-abiding, life-supporting, altruistic behavior. They have no plausible explanation for the development of ethics and truth.

Flew goes so far as to comment, “It would be fair to say that the ‘new atheism’ is nothing less than a regression to the logical positivist philosophy that was renounced by even its most ardent proponents. In fact, the ‘new atheists.” it might be said, do not even rise to logical positivism. Hold on. Let’s take a minute to look at positivism so we’re on the same page as Flew and his argument. Simply stated, it is a Western philosophy that confines itself to the data of experience and excludes a priori or metaphysical speculation. It has also been known as empiricism and, later in the 20th century, analytic philosophy.

WHAT THEY WANT

For the militant atheists, the solution is to weaken the power of faith and religion worldwide and to drive religion completely from the public sphere so that it can no longer have an impact on academia or public policy. In their view, they believe a secular world would be a safer and more peaceful world without the concept of religious faith. D’Souza writes, “Philosopher Richard Rorty proclaimed religious belief ‘politically dangerous’ and declared atheism the only practical basis for a ‘pluralistic, democratic society.’ These ideas resonate quite broadly in Western culture today.”

Isn’t it always a form of child abuse to label children as possessors of beliefs that they are too young to have thought about?—Richard Dawkins

Dinesh D’Souza writes, “It seems that atheists are not content with committing cultural suicide—they want to take your children with them. The atheist strategy can be described in this way: let the religious people breed them, and we will educate them to despise their parents’ beliefs.” In other words, militant atheists are more concerned with indoctrinating our young students against their parents’ religious influence through promoting an anti-religious agenda. It’s been said that Darwinism has enemies mostly because it is not compatible with a literal interpretation of the book of Genesis.

Christopher Hitchens, who was an ardent Darwinist, wrote, “How can we ever know how many children had their psychological and physical lives irreparably maimed by the compulsory inculcation of faith?” Hitchens accused religion of preying upon the uninformed and undefended minds of the young. He did not take kindly to Christian parochial schools. He boldly stated, “If religious instruction were not allowed until the child had attained the age of reason, we would be living in a quite different world.” Sam Harris likened belief in Christianity to a form of slavery! Biologist E.O. Wilson recommended using science to eradicate religion by showing that the mind itself is a product of evolution and that free moral choice is an illusion.

Sam Harris goes further, saying atheism should be taught as a mere extension of science and logic. Harris says, “Atheism is not a philosophy. It is not even a view of the world. It is simply an admission of the obvious. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.” Dawkins believes faith is one of the world’s great evils, comparable to small pox virus but harder to eradicate. He writes in The God Delusion, “Religion is capable of driving people to such dangerous folly that faith seems to me to qualify as a kind of mental illness.” Sigmund Freud regarded religion as a illusion (rather than a delusion, which is a psychiatric term), but he was by no means militant, combatant or completely closed-minded on the subject. In fact, he often invited religious leaders to his home to discuss the merits of their faith. He at least seemed open-minded, albeit not convinced.

Philosopher Richard Rorty argued that secular professors in the universities are out to “arrange things so that students who enter as bigoted, homophobic religious fundamentalists will leave college with views more like our own.” It’s as if these atheist professors intend to discredit parents in the eyes of their children, trying to strip them of their fundamentalist beliefs, making such beliefs seem silly rather than worthy of discussion. D’Souza writes, “The conventions of academic life, almost universally, revolve around the assumption that religious belief is something that people grow out of as they become educated.”

CONCLUDING REMARKS

As children, we certainly spend a great amount of time in school. Basic psychology tells us early child development encompasses physical, socio-emotional, cognitive and motor development between birth and age 8. A continuum of care—from preconception through the formative years—is needed to safeguard and maximize children’s developmental outcomes. Indeed, the first five years of a child’s life effect who a child will turn out to be. The beliefs, emotions, and action-tendencies represent the accumulated experiences people have had while trying to get their needs met, which plays a key role in personality development. Accordingly, personality develops around our motivations (our needs and goals). Children of Christian parents who grow up in an environment that consistently presents and lives the Gospel enter public school with an understanding of Who and What God is. This is more pronounced if they attended a parochial school prior to entering college. Secular professors want to dismantle that belief system in the interest of empirical science and truth.

Militant atheists have come out of the shadows of private belief with the intention of attacking theism in general and Christianity in particular. They are no longer content with deciding for themselves that there is no God. They feel compelled to poison the minds of young college students, steering them away from their faith, by bombarding them with science, logical positivism, Darwinism, pluralism, and moral relativism and… well, whatever works. Just as long as they can convince the world that God is dead one college student at a time.

Praise God that He lives so that we may live.

References

Dawkins, R. (2006). The God Delusion. New York, NY: Bantam Press.

Jeremiah, D. (2011). I Never Thought I’d See the Day! New York, NY: FaithWords.

Pew Research Center. (2019). Age and Distribution Among Atheists. Retrieved from: http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/religious-family/atheist/

Snow, T. (March 13, 2008). “New Atheists are Not So Great.” Christianity Today. Retrieved from: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2008/march/25.79.html